Masters Series No. 5:

Robert Glenn Ketchum

Robert Glenn Ketchum

"A Voice in the Wilderness"

"Endless Meanders, 1998"

from Rivers of Life: Southwest Alaska, The Last Great Salmon Fishery

Photograph © Robert Glenn Ketchum

from Rivers of Life: Southwest Alaska, The Last Great Salmon Fishery

Photograph © Robert Glenn Ketchum

You might not know much about Robert Glenn Ketchum, but his conservation photography and environmental activism have made him one of the most influential photographers of our time.

Posted March 16, 2010

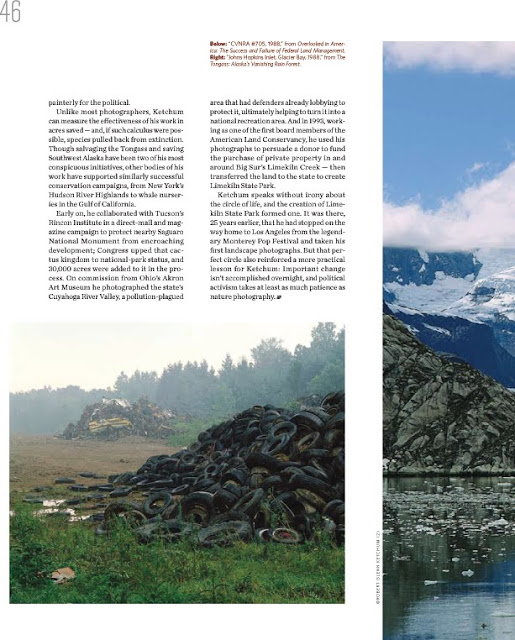

"Rootwads and Slash/Ode to Woodie , 1986" from The Tongass: Alaska's Vanishing Rain Forest

Photograph © Robert Glenn Ketchum

Photograph © Robert Glenn Ketchum

His is not a household name, even in genteel households familiar with photography’s luminaries. He wouldn’t be counted in the firmament of Avedon, Leibovitz, Cartier-Bresson or Helmut Newton, the subjects of American Photo’s prior Master Series issues. Robert Glenn Ketchum, a champion of the modern environmental movement for more than 30 years, may well be the most influential photographer you’ve never heard of.

You probably know the photographers who blazed the trail for Ketchum’s unprecedented use of photography for environmental advocacy — William Henry Jackson, Ansel Adams and Eliot Porter. Just as Jackson’s 1871 photographs of Yellowstone were the argument that convinced legislators to preserve it as America’s first national park, Ketchum’s 1980s photographs of Alaska’s threatened Tongass rainforest were instrumental in leading Congress to set aside a million of its oldgrowth acres as America’s largest national forest — all off limits to logging.

The difference is that unlike Jackson, Ketchum did massive research on his subject and actually lobbied for its cause. Among many other tactics, he visited members of Congress to present them with his newly published Aperture monograph on the Tongass — just as Ansel Adams had worked those hallowed halls in 1936, his own prints in hand, to bring about the establishment of King’s Canyon National Park. And then there is Eliot Porter, whose color photographs celebrated a more intimate kind of natural beauty than Adams’ grand black-and-whites, and who was a mentor to Ketchum until Porter’s death. It is sadly ironic that Porter’s most conservation-oriented work, his photographs of the Colorado River’s Glen Canyon, were published by the Sierra Club only after a massive hydroelectric dam had already flooded the area to create Arizona’s Lake Powell.

“I want my work to be political, like Porter’s,” says Ketchum, whose recent focus has been on photographing and lobbying to protect unsullied Southwest Alaska, in particular the rich fishing grounds of 5.6-million-acre Bristol Bay. “But I never want to be in the position Porter was in, where it was a lament over something already lost.” Indeed, Ketchum means to intervene — in Southwest Alaska and elsewhere — before irreversible damage is done. “I always want to be out in front of an issue,” he says, “so that the work, instead of being about sorrowful regret, can be cutting-edge advocacy.”

While Eliot Porter certainly viewed his photographs as polemical, for him the argument seemed to end once the pictures were seen by the public. For Ketchum, by contrast, photography is just the starting point for an agenda of short-term exhibitions, mass mailings, public events, PowerPoint lectures and other tactics — sometimes subversive but always media savvy — that bring attention to his environmental causes. He traces that key difference with his precursor back to his own MFA work at the California Institute of the Arts. When he was at the school in the mid-1970s, it was a hotbed of politically driven, multimedia performance art, which had picked up where art-forart’s- sake “happenings” left off. “I’ve always viewed my art as a total package,” Ketchum says. “For all the work that the pictures have done, their use was mostly traditional and following in the footsteps of previous historical action.” For Ketchum, though, any performance aspect is for the sake of environmental advocacy, and any advocacy project is multimedia and pragmatic in nature. “Every lecture I give, every press conference I hold, every guerrilla exhibit I throw up in Patagonia store windows is timed to make a difference,” he says.

That total package is also designed to reach larger numbers of people than could be reached with traditional means of photographic dissemination. Yet at the very core of Ketchum’s work is the photographic book, a medium that often limits distribution to no more than a few thousand copies. “Where I feel I changed things and did something different was in working with a nonprofit publisher to turn picture books into advocacy tools,” he says. That nonprofit is Aperture, perhaps the most committed publisher of serious photographic books, which has published seven of Ketchum’s monographs. These include 1985’s The Hudson River and the Highlands, 1987’s The Tongass: Alaska’s Vanishing Rain Forest, 1991’s Overlooked in America: The Success and Failure of Federal Land Management and 2001’s Rivers of Life: Southwest Alaska, The Last Great Salmon Fishery, among others. (See timeline.) Ketchum has taken these handsomely produced books and run with them, getting them into all the right hands — not just those of photography lovers. And with that kind of delivery the photographic book can be a persuasive political tool, condensing visual and verbal arguments into an armchair package.

Ketchum’s artistic thinking is in some ways quite unlike that of traditional nature photographers. He doesn’t force visual drama on his subjects. He tends to avoid familiar devices — such as near-far composition, shallow depth of field, off-kilter framing or toying artificially with the horizon line — that could call more attention to composition and technique than to the simple beauty of his scenes, at least the unspoiled ones.

Yet the seeming lack of a true center of interest in many of Ketchum’s best pictures can be seen as the logical extension of his experience at both UCLA and Cal Arts, which included work in other media. One key influence was Color Field painting, the mid-20th-century practice of creating oversize canvasses containing large areas of flat color, content that made no pretense of breaking out of the picture plane to simulate some other reality. In the 1960s, the movement spread from New York to the far corners of the Western art world, including California. Many of Ketchum’s photographs owe their flatness to this aesthetic — horizonless mountainsides that tip up toward the picture plane, tree trunks that line up with the edges of the frame, aerial views that turn geological features into washes of color. And Ketchum makes that connection clear by printing them at very large sizes.

The images that veer toward abstraction, however, are almost always the ones that depict virginal nature. In what Ketchum calls his “confrontational” photographs — images that show the corruption of nature for our excessive needs — the more-overt message requires a higher degree of realism. These images necessarily sacrifice the painterly for the political.

Unlike most photographers, Ketchum can measure the effectiveness of his work in acres saved — and, if such calculus were possible, species pulled back from extinction. Though salvaging the Tongass and saving Southwest Alaska have been two of his most conspicuous initiatives, other bodies of his work have supported similarly successful conservation campaigns, from New York’s Hudson River Highlands to whale nurseries in the Gulf of California.

Early on, he collaborated with Tucson’s Rincon Institute in a direct-mail and magazine campaign to protect nearby Saguaro National Monument from encroaching development; Congress upped that cactus kingdom to national-park status, and 30,000 acres were added to it in the process. On commission from Ohio’s Akron Art Museum he photographed the state’s Cuyahoga River Valley, a pollution-plagued area that had defendersalready lobbying to protect it, ultimately helping to turn it into a national recreation area. And in 1993, working as one of the first board members of the American Land Conservancy, he used his photographs to persuade a donor to fund the purchase of private property in and around Big Sur’s Limekiln Creek — then transferred the land to the state to create Limekiln State Park.

Ketchum speaks without irony about the circle of life, and the creation of Limekiln State Park formed one. It was there, 25 years earlier, that he had stopped on the way home to Los Angeles from the legendary Monterey Pop Festival and taken his first landscape photographs. But that perfect circle also reinforced a more practical lesson for Ketchum: Important change isn’t accomplished overnight, and political activism takes at least as much patience as nature photography.

Robert Glenn Ketchum: A Life In Photography

1966

Starts college at UCLA, studying with influential photographer-teacher Robert Heinecken; fellow students include Jo Ann Callis and Patrick Nagatani. Pays bills by shooting rock bands, including the Doors and Jimi Hendrix. Shoots first landscapes at Big Sur’s Limekiln Creek on the way home from 1967’s Monterey Pop Festival.

1974

Returns to California after four years of shooting in the Rockies, during which he has earned a living with commercial work and gallery shows. Studies briefly at Brooks Institute, transfers to Cal Arts for MFA in photography. Makes 30-by-40-inch dye transfers, one of the first color photographers to print at such a large scale. Curates shows of vintage work by James Van Der Zee and Paul Outerbridge at Los Angeles Center for Photographic Studies.

1979

Moves to Washington, D.C., to become curator of photography for the National Park Foundation. Organizes exhibit and bestselling book, American Photographers and the National Parks, about the relationship between photographers, the parks and the growth of public environmental awareness. Contributes to first photo exhibit ever held at the White House. Begins to shoot in the forests of the American East.

1983

Moves to New York’s Hudson River Valley to shoot the area on a commission that includes photographers Stephen Shore and William Clift. Starts printing in Cibachrome directly from medium- and large-format transparencies at 30-by-40 inches. Shoots his first “confrontational” images of environmental degradation along the Hudson and elsewhere.

1985

Aperture publishes The Hudson River and the Highlands. Ketchum begins to photograph in Southeast Alaska’s Tongass rainforest, work that shows both the area’s untouched beauty and its increasing despoliation by logging companies. In 1986 is commissioned to photograph Ohio’s Cuyahoga River Valley, a pollution plagued area being proposed as a national park.

1987

Aperture publishes The Tongass: Alaska’s Vanishing Rain Forest. The book is distributed to members of Congress and prints exhibited in the Senate Rotunda. Robert Redford offers Ketchum a three-year artist’s residency at his Sundance Institute in the mountains of Utah. Audubon names him one of 100 people who “shaped the environmental movement of the 20th century.”

1990

Congress passes the sweeping Tongass Timber Reform Act, greatly reducing logging in the rainforest. Aperture publishes Ketchum’s Cuyahoga Valley work in Overlooked in America: The Success and Failure of Federal Land Management. Receives Sierra Club’s Ansel Adams Award for Conservation Photography and, next year, U.N.’s Outstanding Environmental Achievement Award.

1993

Aperture publishes 20-year retrospective of Ketchum’s work, The Legacy of Wildness: The Photographs of Robert Glenn Ketchum. Work is included in CLEARCUT: The Tragedy of Industrial Forestry, which ignites a firestorm of criticism of U.S. forest management. With ALC, funds the creation of Big Sur’s Limekiln State Park.

1994

Organizes multi-photographer exhibit on the Tongass at Smithsonian; prior to its Earth Day opening, Alaska senators Stevens and Murkowski try to censor pictures and text. Ketchum alerts The New York Times, The Washington Post and The Wall Street Journal, all of which publish exposés the next day; the show is unchanged. In 1996 Aperture publishes Ketchum’s Northwest Passage, which brings early attention to global warming.

2001

Aperture publishes Rivers of Life, with which the photographer raises funds for land purchases to protect Southwest Alaska’s rivers and fisheries. In 2002, Alaska says it will permit the open-pit Pebble Mine in the region’s Bristol Bay, creating a 20-square-mile toxic pool that could destroy the bay’s fishing industry. Aperture gives Ketchum its Lifetime Achievement Award.

2006

The Amon Carter Museum mounts Regarding the Land: Robert Glenn Ketchum and the Legacy of Eliot Porter, a retrospective pairing Ketchum with his mentor. Attends a 2007 Washington, D.C., conference on global warming with former House Speaker Newt Gingrich, who supports his Bristol Bay initiative. Hand-delivers Rivers of Life to key U.S. legislators to advance protection for Bristol Bay; John Kerry co-sponsors Senate bill.

2008

During Congress’ Christmas recess, Senator Stevens sneaks Bristol Bay off the bipartisan no-drill list. In January the government offers oil and gas leases in Bristol Bay. In 2009 the Obama administration cancels the leases, but the threat of Pebble Mine remains. Ketchum continues exhibits and shows relating to the bay.

Saving Stitches

“My photographs utilize texture compositionally,” Robert Glenn Ketchum writes in the Fowler Museum’s book Threads of Light: Chinese Embroidery from Suzhou and the Photography of Robert Glenn Ketchum. “Although photographic paper renders them with great fidelity, it does so on a glossy surface, completely devoid of relief. So I found myself increasingly drawn to the idea of translating my complex and highly organic images into textile form.”

Ketchum acted on that idea in 1986, when he first visited China’s famous Suzhou Embroidery Research Institute, just inland from Shanghai. He was met with courtesy and skepticism: The imagery he proposed translating into multicolored stitches was far removed from the traditional subject matter of Chinese embroidery, and the artisans were concerned that it would be too complex and time-consuming to execute. Not one to take no for an answer in his conservation work, Ketchum pressed his case. After some initial tests with simpler images, SERI and Ketchum began an artistic relationship that has lasted more than 20 years.

In accepting Ketchum’s challenge, the institute’s artisans had to expand their language of stitches to simulate photographic effects (see detail, above). Their vocabulary now includes dozens of different kinds of loops, knots and bundles. And Ketchum has asked for ever-larger and more-complex work, including multipanel images that have required several years to complete. The latter are Ketchum’s own nod to their creators’ heritage of elaborately produced standing screens—and the photographer has had them mounted in frames that feature traditional Chinese woodworking. Several are still in process, and more are planned. While not directly related to the environmental agenda that Ketchum has used his images to promote, these unique creations are a reminder that art is at the heart of his work. — Marvin Good

1966

Starts college at UCLA, studying with influential photographer-teacher Robert Heinecken; fellow students include Jo Ann Callis and Patrick Nagatani. Pays bills by shooting rock bands, including the Doors and Jimi Hendrix. Shoots first landscapes at Big Sur’s Limekiln Creek on the way home from 1967’s Monterey Pop Festival.

1974

Returns to California after four years of shooting in the Rockies, during which he has earned a living with commercial work and gallery shows. Studies briefly at Brooks Institute, transfers to Cal Arts for MFA in photography. Makes 30-by-40-inch dye transfers, one of the first color photographers to print at such a large scale. Curates shows of vintage work by James Van Der Zee and Paul Outerbridge at Los Angeles Center for Photographic Studies.

1979

Moves to Washington, D.C., to become curator of photography for the National Park Foundation. Organizes exhibit and bestselling book, American Photographers and the National Parks, about the relationship between photographers, the parks and the growth of public environmental awareness. Contributes to first photo exhibit ever held at the White House. Begins to shoot in the forests of the American East.

1983

Moves to New York’s Hudson River Valley to shoot the area on a commission that includes photographers Stephen Shore and William Clift. Starts printing in Cibachrome directly from medium- and large-format transparencies at 30-by-40 inches. Shoots his first “confrontational” images of environmental degradation along the Hudson and elsewhere.

1985

Aperture publishes The Hudson River and the Highlands. Ketchum begins to photograph in Southeast Alaska’s Tongass rainforest, work that shows both the area’s untouched beauty and its increasing despoliation by logging companies. In 1986 is commissioned to photograph Ohio’s Cuyahoga River Valley, a pollution plagued area being proposed as a national park.

1987

Aperture publishes The Tongass: Alaska’s Vanishing Rain Forest. The book is distributed to members of Congress and prints exhibited in the Senate Rotunda. Robert Redford offers Ketchum a three-year artist’s residency at his Sundance Institute in the mountains of Utah. Audubon names him one of 100 people who “shaped the environmental movement of the 20th century.”

1990

Congress passes the sweeping Tongass Timber Reform Act, greatly reducing logging in the rainforest. Aperture publishes Ketchum’s Cuyahoga Valley work in Overlooked in America: The Success and Failure of Federal Land Management. Receives Sierra Club’s Ansel Adams Award for Conservation Photography and, next year, U.N.’s Outstanding Environmental Achievement Award.

1993

Aperture publishes 20-year retrospective of Ketchum’s work, The Legacy of Wildness: The Photographs of Robert Glenn Ketchum. Work is included in CLEARCUT: The Tragedy of Industrial Forestry, which ignites a firestorm of criticism of U.S. forest management. With ALC, funds the creation of Big Sur’s Limekiln State Park.

1994

Organizes multi-photographer exhibit on the Tongass at Smithsonian; prior to its Earth Day opening, Alaska senators Stevens and Murkowski try to censor pictures and text. Ketchum alerts The New York Times, The Washington Post and The Wall Street Journal, all of which publish exposés the next day; the show is unchanged. In 1996 Aperture publishes Ketchum’s Northwest Passage, which brings early attention to global warming.

2001

Aperture publishes Rivers of Life, with which the photographer raises funds for land purchases to protect Southwest Alaska’s rivers and fisheries. In 2002, Alaska says it will permit the open-pit Pebble Mine in the region’s Bristol Bay, creating a 20-square-mile toxic pool that could destroy the bay’s fishing industry. Aperture gives Ketchum its Lifetime Achievement Award.

2006

The Amon Carter Museum mounts Regarding the Land: Robert Glenn Ketchum and the Legacy of Eliot Porter, a retrospective pairing Ketchum with his mentor. Attends a 2007 Washington, D.C., conference on global warming with former House Speaker Newt Gingrich, who supports his Bristol Bay initiative. Hand-delivers Rivers of Life to key U.S. legislators to advance protection for Bristol Bay; John Kerry co-sponsors Senate bill.

2008

During Congress’ Christmas recess, Senator Stevens sneaks Bristol Bay off the bipartisan no-drill list. In January the government offers oil and gas leases in Bristol Bay. In 2009 the Obama administration cancels the leases, but the threat of Pebble Mine remains. Ketchum continues exhibits and shows relating to the bay.

Saving Stitches

“My photographs utilize texture compositionally,” Robert Glenn Ketchum writes in the Fowler Museum’s book Threads of Light: Chinese Embroidery from Suzhou and the Photography of Robert Glenn Ketchum. “Although photographic paper renders them with great fidelity, it does so on a glossy surface, completely devoid of relief. So I found myself increasingly drawn to the idea of translating my complex and highly organic images into textile form.”

Ketchum acted on that idea in 1986, when he first visited China’s famous Suzhou Embroidery Research Institute, just inland from Shanghai. He was met with courtesy and skepticism: The imagery he proposed translating into multicolored stitches was far removed from the traditional subject matter of Chinese embroidery, and the artisans were concerned that it would be too complex and time-consuming to execute. Not one to take no for an answer in his conservation work, Ketchum pressed his case. After some initial tests with simpler images, SERI and Ketchum began an artistic relationship that has lasted more than 20 years.

In accepting Ketchum’s challenge, the institute’s artisans had to expand their language of stitches to simulate photographic effects (see detail, above). Their vocabulary now includes dozens of different kinds of loops, knots and bundles. And Ketchum has asked for ever-larger and more-complex work, including multipanel images that have required several years to complete. The latter are Ketchum’s own nod to their creators’ heritage of elaborately produced standing screens—and the photographer has had them mounted in frames that feature traditional Chinese woodworking. Several are still in process, and more are planned. While not directly related to the environmental agenda that Ketchum has used his images to promote, these unique creations are a reminder that art is at the heart of his work. — Marvin Good